Sol Koffler Gallery

169 Weybosset St.

PVD, RI

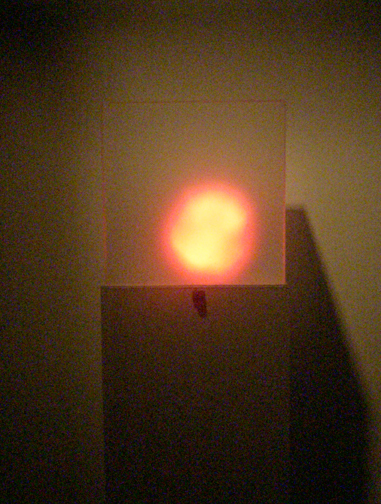

[Acrylic box, red light bulb, wood pedestal, acrylic paint, dimmer, proximity sensor, microcontroller]

My body is paralyzed. It rushes blood to my cheeks because I have dared to be vulnerable, and everyone can see me.

E. L. Constable wrote a very interesting essay centered on the concept of shame employed by the French writer and philosopher Albert Camus extracted from his writings. Although Camus’s position was more political and derived from a collective relationship as a nation with his characters, he envisions shame as a process of becoming sympathetic with the experience of guilt, an event from which one can learn and grow from. To make this point valid, he quotes Silvan Tomkins, a psychoanalyst whose writings from the sixties were compiled in the mid-nineties into a book called Shame and his Sisters (Kosofky, E., 1995):

“Why is shame so close to the experienced self? It is because the self lives in the face, and within the face the self burns brightest in the eyes. Shame turns the attention of the self and others away from this most visible residence of the self, increases its visibility, and thereby generates the torment of self-consciousness (136) (Constable, E.L., 1997).”

A terrible torment indeed, the negative motivation behind the piece was this possibility of displacing a psychosomatic experience to a machine that mechanically blushes. It was a way of abstracting the essential elements that express a human emotion through an electric impulse. By being looked at or by approximation one blushes, that is, one feels incapable to be scrutinized and instead of turning that feeling into a positive experience of admiration, it becomes helation in Medusa’s disapproving gaze of rejection.

Clearly what distinguishes a man from any other creature on Earth amongst other things, is blushing. Men have always sought to create machines that in short, can become human. The attempt for this piece is conceptually not far from the efforts of Alan Turing or Vannevar Bush but they are clearly not related in the systemic organization of information nor in artificial intelligence. My work exists in the poetic empathy that is generated towards the machine.

The Blushing Machine is a triangular pedestal with an acrylic top. Inside the acrylic box resides a red light bulb connected to dimmer receiving information from a proximity sensor and regulated by a microcontroller. These connections have always made me aware of how humans name technological objects towards their function. Given the relevance of gaze or physical proximity as triggers for setting off a blushing experience, this piece has three electronic components that mimic the physiological processes in the body.

The proximity sensor reads the distance of the viewer, in relation to the other person in a determined space. This sensor sends a signal to the microcontroller, which is the brain of the machine. It tells the dimmer how close a person is and fades the light bulb in or out depending on this value, just as an adrenaline rush would reach the cheeks or make one’s hands sweat. Once the viewer walks away from the piece, blushing slowly fades away. There is immediate relief in oblivion.

Special Thanks to Mónica Martínez and beautiful Max.