Cyberarts Festival 2008

April 24 – May 10, 2009

1330 Boylston St., Boston, MA

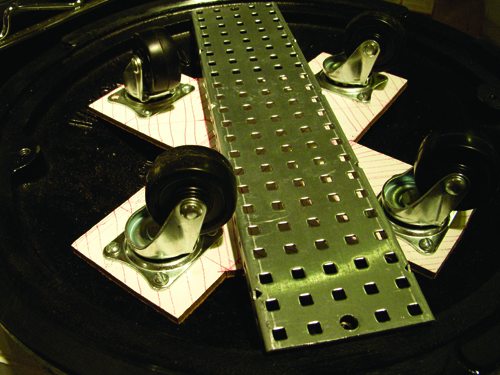

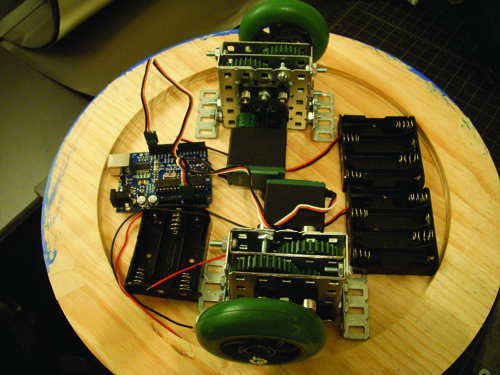

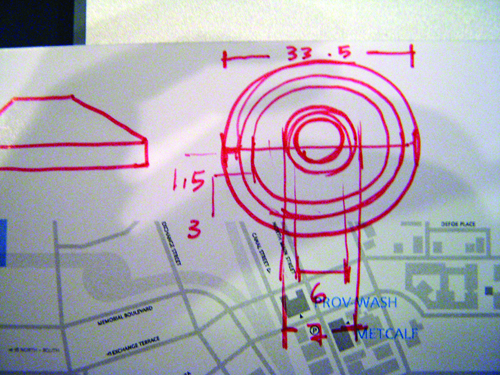

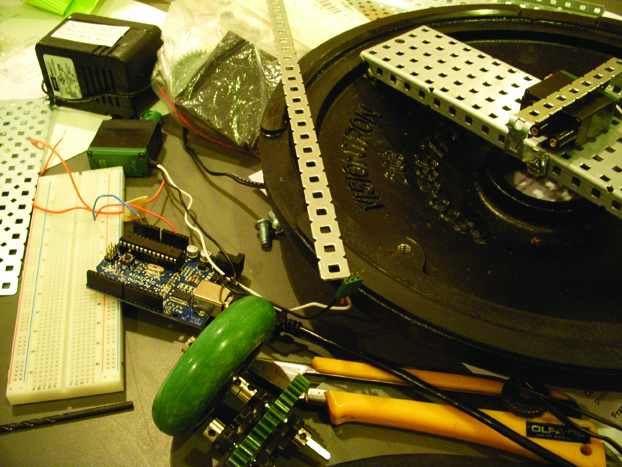

[Wood, automotive painting, microcontrollers, batteries, wheels, belt]

In our pre Hispanic past we had a world. One that was based on duplicity, our Gods had qualities of creation and destruction (Gingerich, W., 1998). We relied on the cycling elements of the earth, were limited by our omens and celebrated our victories. If we heard an owl it was a sign of death, every new year was a conquest over death as the end of each was associated with doom. We looked at the stars and our spaces were conceived to interact with the passing of light, fixed stones became alive with moving shadows.

Then four legged Gods arrived from the sea. They were like nothing we had seen before. They could become two beasts: a two-legged one that spoke in some other language and another one that neighed. As part of their bodies, they had sticks that spat darts of fire, we were dazzled and terrified by those who called themselves Spaniards.

Otherness. What a powerful moment.

“Otherness informs human existence, marking it with ambiguity, indeterminancy, and incommensurability. It is a presence but also an absence or awayness, a constancy of difference challenging and clashing with one’s sense of core identity. That it is always there–away from us as something other–makes it also here, for absolute apartness or absence would render it imperceptible and unknown” (Grandy, D., 2001).

In reference to the Spanish Conquest, de Certeau explains how “[the indigenous people] were [the] other within the very colonization that outwardly assimilated them; their use of the dominant social order deflected its power, which they lacked the means to challenge; they escaped it without leaving it. The strength of their difference lay in procedures of “consumption” (De Certeau, M., 1984).

On my way back from Mexico after spring break in 2008, my mind was thinking about borders and limits, migration and space. While I was in line waiting for the US customs to let me through, on my left, people from the U.S. filled the line where retractable crowd barriers demarcated the space. They had an unquestionable serpent-like flow through these barriers until they stopped, then the line was emptied and once again, that repetitive pattern continued.

In the process of understanding this grid, I came across an NPR Interview with Richard C. Larson professor of Engineering Systems and Civil & Environmental Engineering about how much time was spent waiting in lines. His essay, Perspectives on Queues: Social Justice and The Psychology of Queueing opened a new outlook on the perception of “Empty Time”:

“Waiting is a form of imprisonment. One is doing time-but why? One is being punished not for an offense of one’s own but for the inefficiencies of those who impose the wait. Hence the peculiar rage that waits engender, the sense of injustice. Aside from boredom and physical discomfort, the subtler misery of waiting is the knowledge that one’s most precious resource, time, a fraction of one’s life, is being stolen away, irrecoverably lost” (Larson, R., 1987).

Mexican Retractable Crowd Barriers became a possibility of breaking the system behind queueing. It seemed obvious that without people’s intervention, these objects already spoke of waiting in line. The question then was if by the animation of these objects I could create dynamic changes and thus the participation of people under institutional patterns of order in a constant and evolving flux of playful anarchy. As Deleuze would propose: “To be rhizomorphus is to produce stems and filaments that seem to be roots, or better yet connect with them by penetrating the trunk, but put them to strange new uses” (Deleuze, G., 1987).

Special Thanks to: Richard C. Larson, Proffessor of Engineering Systems and Civil & Environmental Engineering, Jim Tabele from the Old-Fashion Robotic Store in PV, RI and Taehee Kim for the programming of the piece.